First Principles What It Means and What Leaders Say - Day 188

Imagine you want to fix a clock, but you’ve never taken one apart. You can copy someone else’s fix, or you can open the clock, look at the gears, and ask: “What actually makes this thing tick?” That second path breaking a problem down to its simplest parts and building up from there is called first principles thinking. It’s a way to stop repeating old habits and start inventing better solutions.

Below I’ll explain what first principles means, what a few famous leaders have said about it, and a few concrete ways you can use it every day.

What first principles thinking really is

First principles means stripping a question down to the basic facts you can’t argue with, then reasoning up from those facts. Instead of thinking “we do it this way because everyone does,” you ask: “What are the true constraints? What is absolutely required?” It’s simple in idea and powerful in practice.

What top leaders have said

Elon Musk: He talks about using physics as a guide - asking what something is made of and what the raw parts cost, instead of accepting the usual price tags or traditions. Musk says it helps you find new, cheaper, or faster ways to solve problems.

Peter Thiel: In Zero to One, Thiel praises first-principles thinking as the way founders find real value in places others ignore. He says successful people don’t just copy; they look for hidden truths and build from there.

Charlie Munger: Munger stresses the need for a “latticework” of ideas simple building blocks from different fields to make sense of things. He warns that without fundamental models, facts stay isolated and useless.

Richard Feynman: The physicist put it bluntly: the first principle is to avoid fooling yourself. Be honest about what’s true; that honesty is the foundation for any reliable thinking.

Why leaders like it

It forces clarity.

It opens up real options instead of copies.

It cuts hidden costs and assumptions.

It helps build breakthroughs, not small improvements.

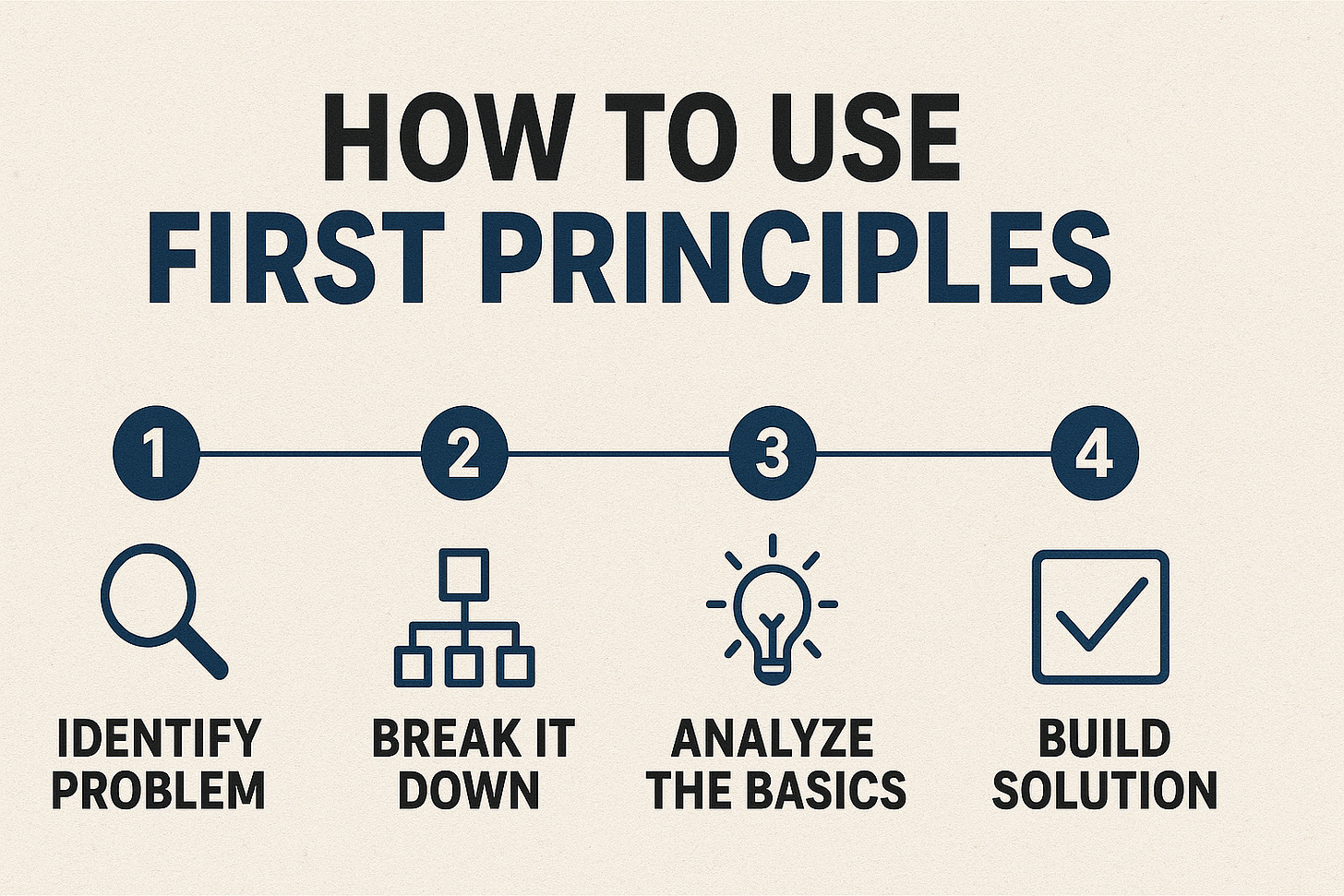

How to use first principles 4 simple steps

Identify the question.

Example: “Why is this product so expensive?”Break it down to basic facts.

Ask: what are the essential parts or truths? (materials, labor, distribution, regulations)Challenge assumptions.

Don’t assume those parts must cost what they do. Ask: Can something else do the job? Can we combine steps?Rebuild from the ground up.

Use the facts to design a cheaper, faster, or simpler solution.

Example in everyday life: Want to save ₹5,000 a month? Break down your spending into essentials, wants, and wasted steps. Replace one “want” with a cheaper option and automate the savings.

Example in investing (since you like finance): Instead of copying a popular stock pick, start with the business’s core cash flows. What does the company actually sell? How much does it cost to make? What are durable advantages? Build a view from those basics, not from headlines.

Things people get wrong about first principles

They think it’s only for scientists or billionaires. (Nope, it’s a clear habit anyone can practice.)

They confuse it with being contrarian for the sake of it. First principles isn’t “do the opposite”, it’s “do what the facts support.”

They skip the hardest step: being brutally honest about what you don’t know. That’s exactly what Feynman warned about.

What I’d add practical tweaks you can use today

Carry a one-question notebook. When a decision pops up, write the single most basic fact behind it. Revisit weekly.

Use friendly cross-checks. Ask someone from a very different field to explain your idea in plain words; their questions often reveal hidden assumptions.

Set a “reverse checklist.” List the usual reasons people accept a thing. For each, write a short counter fact or question that helps you poke holes cleanly.

Small experiments beat big guesses. Test the cheapest version of your idea quickly (a prototype, a short survey, a one-week trial). Real feedback forces honest first principles thinking.

Short closing: why this matters for you

First principles thinking turns vague worries into clear tasks. It’s less about being clever and more about being clear. Leaders like Musk, Thiel, Munger, and Feynman used it in different ways: engineering, startups, investing, and science but the backbone is the same: strip away fluff, face the facts, build from there. If you make that a habit, your decisions will get simpler and better.